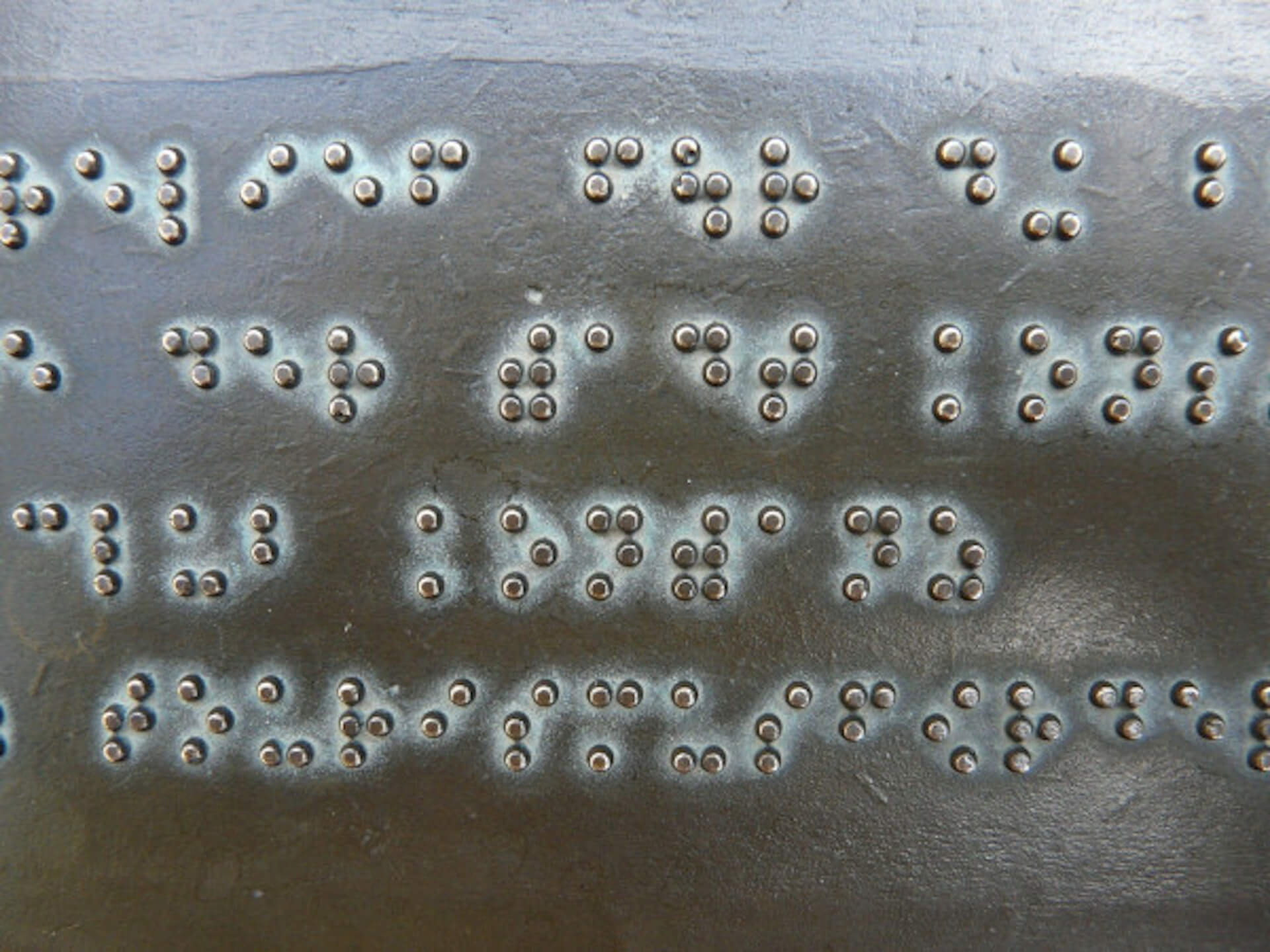

On elevators, medicine boxes, descriptions in museums or door signs…, you’ve probably noticed those small raised dots. You already know they’re for blind people but do you know how they work? Let us guide you through it!

Braille, the writing and reading tactile system with raised dots used by visually impaired people, exists since 1829. Its inventor, Louis Braille, a French blind man, created this tactile alphabet in order to be able to read and write, thus gaining access to education like everybody else. Braille represents an essential tool for a visually impaired person to learn and consequently be included in society. Even though braille has evolved, the 1829 system still constitutes the reading basis for blind and visually impaired people. Let’s go back in time to discover its creation and its use in today’s society!

Systems used before Braille

As soon as the 17th century, it has been understood that the sense of touch for blind and visually impaired people was to be exploited to teach them how to read. The idea of touching embossed paper came from Italian Jesuit Francesco Lana de Terzi with its eponymous system in 1670. The Lana system was composed of lines and raised dots on thick paper based on a three-by-three grid containing the alphabet letters. One just needed to learn the specificities of this grid to learn this writing system.

In the following century, French man of letters Valentin Haüy made education for blind and visually impaired people really possible. He had special embossed and movable characters made so that students could touch and read what was under their fingers. This raised letters method was put into practice at the Royal Institution of Blind Children, now called the National Institute for the Young Blind, a school opened by Valentin Haüy in Paris in 1785. The Valentin Haüy Association that also emerged still continues to promote Braille.

Although the two previous systems were specifically designed to meet the needs of blind and visually impaired people, 1808-1809 code by French Charles Barbier de la Serre was first created for army officers so that they could write and transmit messages in the dark. Called “night writing”, this system was based on sounds and consisted of raised dots on a grid. In 1819, Barbier perfected it to present it at the Royal Institution of Blind Children.

Louis Braille, at the time a student of the school, perceived the system potential but also its limits since it didn’t take into account the words spelling but only their pronunciation. He decided to improve Barbier system himself seeing that Barbier didn’t agree with his suggestions. He then created a code still used today and lent it his name: Braille.

What is Braille?

Louis Braille kept the basic principles of Barbier system, that is to say the encoding and the raised dots, but reviewed two elements:

⊗ The number of dots went from 12 to 6.

⊗ He opted for the coding of Latin typographic signs (letters, punctuation, musical notes).

Where a non-visually impaired person sees an indecipherable, crypted and almost extra-terrestrial language, a visually impaired person perceives a distinct language, a code they decipher and master to read and to learn. We tend to forget it but Braille is indeed a code! Continuing with an encoding enables to keep a system that’s easy to learn: each character is set in a cell composed of raised dots. In a cell, the six dots are divided into two columns. The numbering of dots allows to know their position. Thus, each character has a very precise combination.

Braille is a universal language since it’s used by other Latin languages for basic letters but there are still elements that can differ according to the languages such as accented letters, symbols and punctuation signs.

Despite being a code, it still needs to render the meaning of the language used: consequently the meaning of the symbols isn’t the same according to the language. That is why Japanese, Korean and Cyrillic brailles have different particularities that set them aside from French Braille.

Code developments

Gradually, the code has evolved and impacted other areas such as mathematics and music thus enabling blind and visually impaired people to develop skills and/or hobbies. Nevertheless, there are limits to mathematics Braille. Mathematics formulas can indeed be very long once transcribed into Braille and therefore complex to comprehend.

Seeing that the standard Braille and its 6 dots only permits having 64 combinations, some characters such as numbers or capital letters have to be coded onto 2 characters. When Braille moved to IT, the Braille cell thus gained 2 dots. Thanks to this IT Braille encoded on 8 dots, 256 combinations are then possible, which enables to transcribe all the new symbols of the digital era such as the at symbol into just one character.

A system that looks to the future

Today, visually impaired people can easily be connected to the Web and thus to the entire world same as any Internet user. Technology has evolved and serves them. It’s not just smartphones that enable them to gain a real autonomy. Thanks to the advanced progress, blind and visually impaired people can:

⊗ Read any document on the net thanks to a Braille transcription software. The text is automatically transcribed into Braille and can even be printed in Braille thanks to a special printer called braille embosser.

⊗ Access scanned Braille documents thanks to the National Library Service (NLS) and other digital libraries.

⊗ Use a refreshable Braille display (or Braille terminal) on which a Braille keyboard is embedded. The dots can raise or lower depending on the characters. The onscreen text can directly be translated unto the refreshable Braille display.

⊗ Set up a speech synthesizer that reads aloud the onscreen text.

⊗ Use a screen reader software that transforms the onscreen text into a Braille page or into a read aloud text.

Looking into the history of Braille and its evolution, it’s easy to realize that Louis Braille has truly changed millions of people lives giving them access to an education, a fundamental right. He literally gave them the keys, well the code, so that they can live in a more inclusive world with real autonomy. His code enables blind and visually impaired people to read, write and learn just like any citizen and is used today to comply with the demands of the digital world. From 1829 to 2020, just a few clicks are enough…

media

Braille represents an essential tool for a visually impaired person to learn and consequently be included in society. Even though braille has evolved, the 1829 system still constitutes the reading basis for blind and visually impaired people.

writer

Carole Martinez

Content Manager

stay updated

Get the latest news about accessibility and the Smart City.

other articles for you

Open Data Is Key to Fostering Universal Accessibility

Open data represents an opportunity for cities to reach universal accessibility. It shows the missing links of the mobility chain.

Our Audio Beacons Guide the Blind and Visually Impaired at the Helsinki Subway

The Helsinky subway improved their audio signage system by installing on demand and remotely activated audio beacons.

7 Good Reasons to Install Audio Beacons at Your Public Transport Network

Audio beacons are an efficient way to provide more autonomy to blind and visually impaired people. They can easily use public transport.

Will Remote Activation Become the Norm for Accessible Pedestrian Signals?

More and more cities like New York have been exploring remote activation to trigger accessible pedestrian signals.

share our article!

more articles

Disability Statistics in the US: Looking Beyond Figures for an Accessible and Inclusive Society

Disability Statistics in the US: Looking Beyond Figures for an Accessible and Inclusive Society Around 61 million adults in the United States live with a disability. Diving into disability statistics in the US will help us know exactly who is concerned and what...

Our Audio Beacons Guide the Blind and Visually Impaired at the Helsinki Subway

Our Audio Beacons Guide the Blind and Visually Impaired at the Helsinki SubwayOur audio beacons equip the new line of the Helsinki subway in Finland. They help blind and visually impaired people locate the points of interest of a station. For users with visual...

Will Remote Activation Become the Norm for Accessible Pedestrian Signals?

Will Remote Activation Become the Norm for Accessible Pedestrian Signals?Without pushbutton, there are no accessible pedestrian signals. That’s how APS work in the U.S. But more and more cities have been exploring remote activation like New York City. The Department...

Hearing Impaired People: a Multitude of Profiles for Different Needs

Hearing Impaired People: a Multitude of Profiles for Different Needs Did you know that hearing impaired people have several profiles and that the way they identify themselves is important? You may be familiar with deaf and hard of hearing people but for each of...

NEVER miss the latest news about the Smart City.

Sign up now for our newsletter.

Unsubscribe in one click. The information collected is confidential and kept safe.

powered by okeenea

The French leading company

on the accessibility market.

For more than 25 years, we have been developing architectural access solutions for buildings and streets. Everyday, we rethink today’s cities to transform them in smart cities accessible to everyone.

By creating solutions ever more tailored to the needs of people with disabilities, we push the limits, constantly improve the urban life and make the cities more enjoyable for the growing majority.